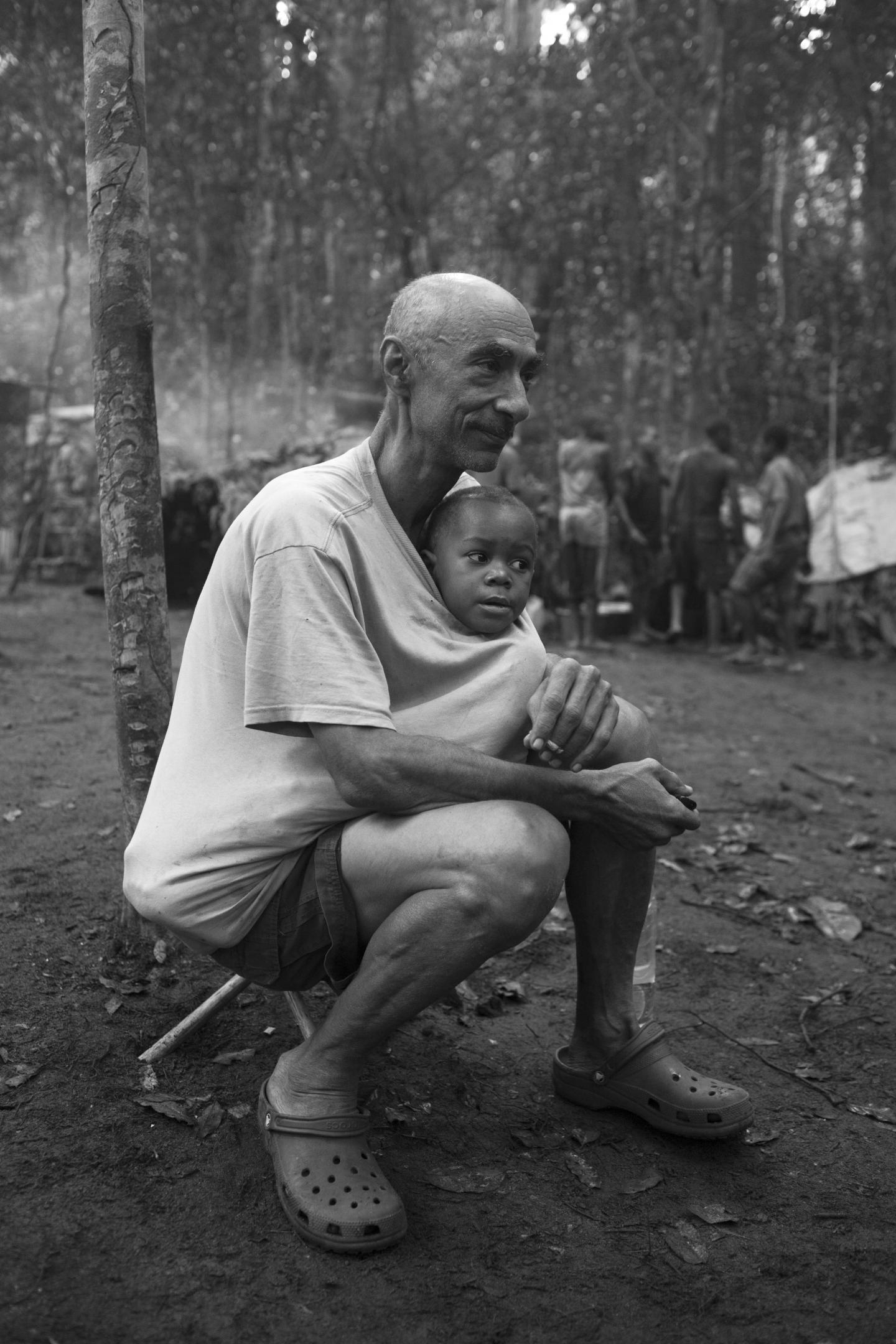

Louis with BaAka child. Photo by Matthias Ziegler

Read this gorgeous article Inside the Word of Louis Sarno the Pygmy Chief From New Jersey

Jump to the different sections by clicking on one of the following buttons :

Song From The Forest - The Film

Director Michael Obert released the documentary, Song From The Forest about Louis' time with the Bayaka pygmies:

Song From The Forest in the Press:

International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam | Politiken Magazine (in Danish)

About Louis Sarno

Louis Sarno was born in New Jersey, USA. For 30 years he lived amongst the BaAka peoples, in the Central African Republic, one of the poorest countries in the world.

In his own words, this is how it began for him:

“I was drawn to the heart of Africa by a song. Alone one evening in an apartment I'd just secured in a northern European capital, I switched on the radio in time to catch a program of traditional African mourning songs. Serendipity was in the air that night: a blank cassette happened to be in the radio/cassette player, and for the first time in my life I recorded a radio program. Afterwards, listening to that tape many times over, I grew obsessed by one song in particular—an Aka lament.

I went on to locate and record every commercially available vinyl album of the music of the (for want of a generalized term) African pygmies -- the Efe, the Baka, the Aka, the Mbuti, etc. When I'd exhausted what was commercially available I made appointments with ethnographic museums in order to talk my way into their record collections, where I found and recorded several valuable but long out-of-print albums. Next I approached university anthropology departments, hoping to gain access to their vast collections of field recordings, but they rebuffed me. How could I explain that I was a pygmy music junkie? In the end, I succumbed to the inevitable and came to Africa to make my own recordings (more than 1000 hours now), and I've been here ever since (26 years and counting).

I live in a community of BaAka, hunter-gatherers of the rain forest. The BaAka still spend several months each year in forest camps, hunting small game with nets, spears, and crossbows; gathering honey, wild yams, vegetables and fruits; and making music.

Part of the year they spend in roadside settlements. Formerly, these settlements were little more than squats on land owned by non-Aka Africans. In return for permission to live on the land, the BaAka cultivated manioc gardens for the land owners and did other chores. Nowadays, the community has its own village on land I purchased. The community has grown from nearly a hundred people when I first came, to more than six hundred. Many families now cultivate their own manioc gardens, and plant other crops as well, including corn, bananas, groundnuts, and jackfruits.

Most of the people around me are the children of my original friends here, many of whom have died. Their children have grown up, and now have children of their own. My life long ago veered from the single-minded quest for music, as I became ever more intimately involved with the community.

Since this village is my home, I devote myself to helping it face the complicated challenges posed by the 21st century. I struggle with the education dilemma of creating a curriculum that causes as little disruption to their traditional activities as possible. I have funded the school we have in our village even though the school program is far from ideal. For years at a time, I have been the only medical resource my community has access to. The situation is a little better now with the establishment of a local health center, but I'm still the one who foots most of the bill. Clean drinking water, not a problem in the forest where we drink from unpolluted streams, is increasingly an issue in the village. We have one pump and will soon be acquiring a second.

The BaAka cope with racism from other ethnic groups, and consequently a justice system often skewered against them. There are conflicts over access to forest resources. I work with these issues on a daily basis. All my resources now go towards helping my adopted community negotiate a future through this onslaught of outside forces.

The biggest overall change since I first came here is the growth in population of the nearby (non-Aka) town, and especially the arrival of the commercial bush meat trade. The animals in the BaAka's forest are being slaughtered by hunters with shotguns who hunt the animals to export their meat. The monkey population has been decimated, and the duiker (small forest antelopes) population has been very hard hit (this despite the presence of a WWF-sponsored conservation program). Duikers are the BaAka's primary source of protein in the forest. They hunt them using nets.

In my early years I spent so much time in forest camps I didn't bother to own a house in the village. I've had some great adventures. Thinking about them these days when I'm confined much more to village existence because of my social responsibilities (which include raising three children right now) provides some compensation for my more sedentary way of life. In any case, with all the poaching, the forest has become a much sadder place for me. I spend much of my time these days puttering about in my small fruit-tree orchard. Usually, at any given moment, at least one gang of children can be found in my trees, checking out the fruit. They're welcome to anything they find, as long as it's ripe. I myself have yet to eat a single fruit from the orchard. The children always get to it first, and that's how it should be.

I don't work for any organization or religion. But I live here, as a naturalized citizen of the Central African Republic. I am distressed by certain possible scenarios of the future, so I do everything within my limited capacity to help make the future a good one for the BaAka. Other than the little jobs that come my way, such as guide and facilitator for occasional tourists or film teams wanting to go into the forest, I'm completely dependant on donations. These can be made through the Global Voice Foundation.”—Louis Sarno, 2016

Lost and found in the forest

Interview

By Mark Wilshin, Exberliner, September 9, 2014

A song on the radio led American Louis Sarno to the Central African rainforest. Twenty-five years later, Michael Obert found him there.

In his debut documentary Song from the Forest, Obert, a Berlin-based journalist turned filmmaker, follows Sarno and his son Samedi as they journey from their home among the Bayaka tribe to the US.

Adventurer, journalist, writer, filmmaker – how would you describe yourself?

Storyteller. Or traveller and storyteller maybe. I think travelling brought me to writing, and writing brought me to filmmaking basically. But it’s mainly my interest in stories of human beings. I like these stories that ask existential questions basically, and that make me think about my own life, my own path, my own story, my own decisions. And that’s the way I write my stories.

Song from the Forest is your first film. You must have faced a lot of challenges…

No electricity, obviously. No running water. Dense vegetation. It’s always dark, incredibly humid. But the biggest challenge was shooting in the US, because of Louis’ deep culture shock. Very often I had to leave the camera and just turn from filmmaker to human being, to friend. To support him. I think that was a lot harder than anything we experienced in the jungle.

How does that work? How do you know when to put the camera down?

I don’t really consciously reflect on this. If I feel if this is a moment to help and act in a human way, then I just act. I think my filmmaking and my journalistic work is always happening on a very human level. At eye-level. So the people I’m dealing with, they usually trust me. I don’t want to disappoint them when they need my help.

It’s a nostalgic film about lost people – both Louis Sarno and the Bayaka. Do you think a documentary film can do more than just document?

Personally, I don’t care about genre definitions. I like to treat the subject almost as if it was a feature film. I hate talking head films. I hate the whole biopic thing as well. For information, you can just go online. It’s definitely not a film about answers. I hate answers in movies. It’s a poetic work, and poetry is all about space I think. So the movie opens spaces and you can wander around the spaces as an audience, and then you come out with your questions. That’s the type of storytelling I’m interested in.

It’s very observational and spontaneous – do you have a favourite moment?

What really touches me still is whenever the 16th-century music comes up. The whole idea to use William Byrd’s Mass for Four Voices as the backbone of the whole movie, it’s an experiment, but I think it worked out really well.

What’s the story behind that music?

That first night after our encounter, he took me to his hut and we were talking randomly for hours. At one point, I was so exhausted I just lay down on the earth floor, and maybe a couple of hours later I woke up and I heard this music, the first piece that we use to open the movie – the Kyrie of the Mass, sung by the Oxford Camerata. I had the feeling I was between a dream and reality. And then I opened my eyes and saw Louis at his worm-eaten table in the Rembrandt light of his lantern listening to this music, and I got goosebumps. I think the music Louis had heard on the radio lured him into the rainforest, but this music lured me into his life. It will be five years ago this autumn, and I’m still there. He’s a major part of my life, I’m a major part of his life. He’s my rainforest, basically.

Louis Sarno - 20 Questions

Interview

By Deni Kasrel, Philadephia Citypage, June 13, 1996

Background: Perhaps growing up in Newark, New Jersey, had something to do with it, but in the late 1980s Louis Sarno reckoned he had had enough of this so-called civilized life, opting to live in central Africa with a Pygmy tribe known as the Bayaka. Sarno originally visited these hunter-gatherers to learn more about their music, which he'd grown attracted to and wanted to hear in person. Besides being drawn to the Bayaka's riveting music, Louis derived great satisfaction from their simpler way of life, most especially from the hunting expeditions into the rain forest.

Sarno is now married to a native Bayakan and he's allowed to witness special ceremonies and rituals never before seen by an outsider. With the aid of Bernie Krause, a producer who has recorded natural sounds of the forest and oceans since 1968, he combined recordings of Bayakan music with sounds of their surrounding environment into a two-CD/book package entitled Bayaka: The Extraordinary Music of the BaBenzl Pygmies (Ellipsis Arts).

The music is emotional and spiritual, with women singing complex interweaving harmonies while men beat out polyphonic accompaniment on instruments made of vines, hollowed-out logs and animal skins. In the companion book Sarno illuminates the Bayakan people in words and pictures. Recently there has been outside pressure to assimilate the Bayakan to Western ways, and Sarno's efforts represent a living document of a vanishing people.

What were you doing before you got involved with the Bayakan people?

I was dividing my time between Holland and Scotland. In Holland I did work like typing up people's books, editing English translations, and in Scotland I did seasonal work on a farm with sheep and Christmas trees. Before that I was a graduate student at the University of Iowa studying comparative literature and then mathematics. In 1984 I traveled to North Africa to make recordings of Berber music and also went to Egypt looking for music of the nomadic Bedouin, and at the end of 1985 I went to Central Africa.

What was your interest in going to Africa to record this music?

I became fascinated with the music of the rain forest all over the world and particularly different Pygmy groups. I had gotten some recordings, but it wasn't satisfactory to me and I began to believe there was a lot more music than was available on records.

It would seem they'd be wary of an outsider becoming one of their community. How did you fit in?

It was difficult. My thing was I loved their music. For me, it's like maybe if I knew Beethoven. Maybe Beethoven was in many ways a very trying person, but if you loved his music enough you'd put up with all of that and make an effort to be liked by him. Maybe the Bayaka did try and shake me off in the beginning but I wasn't aware of it and they eventually came to accept me.

How do you live there — what's your space like?

I have two modes of existence. One is in the settlement along the road and the other is in the hunting camp in the forest. In the settlement the houses tend to be built with bamboo poles and palm leaves or thatching for the roof. Then you make a bed with bamboo poles and a mat. In the forest there's these beehive huts that are so small I can't stand up in them and also a bed platform made of poles.

What was it like going into the forest for the first time? Were you scared?

I loved the forest from the first instant I stepped into it. I was never frightened. I never understood these 19th-century accounts about going in the jungle and pushing oneself to the last ounce of their strength and there's these bees and they sweat beads. They make it sound like a hell on earth. That's nonsense. It's paradise. I love the rain forest. I feel protected in it.

What's the longest stretch you've stayed in the forest?

Three months.

What's it like to step out of it after that length of time?

I'm always disappointed coming out of the forest, because in the forest it's cool, it never gets too hot. When you step out on a sunny day, it's like stepping into a furnace. I love the sounds of the forest — the birds, the monkeys, the fragrances, the tree blossoms.

This project has different recordings from the Boyobi ceremony. What's that like?

It's the hunting ceremony. It's held to call to bob, these special spirits to protect the hunters or to insure they get some food. It involves all the members of the community. The men are the ones who transform into the spirits and they do the drumming. The women and children are the choir. The bob have two basic forms. One is they clothe themselves in leaves, and with the other they come in these luminescent designs, like forms of animals and strange faces all glowing. They use luminescent mold that grows on the inside of tree bark. You can have up to twenty glowing figures, each one different. They sing in these falsetto voices and they dance to the music. It's an incredible show.

Some people think of Pygmies as a primitive culture, but you don't, right?

Well, how do you measure primitive? I think Bosnia is primitive. I don't think the Bayaka are primitive just because they don't have advanced technology. Their technology is successful for their way of life and they've never fought a war. War to me is barbaric and true primitivism.

Do you think they represent a kind of enlightenment?

I think their society is very enlightened in many aspects as compared to our lives. We have these technological accomplishments, but it doesn't really tell us how to live. Life is so needlessly complicated in modern society. It's more simple in the rain forest. The Bayaka don't need psychiatrists. They don't need Prozac.

There's outside pressure to modernize Bayaka culture, and also, conservationists are limiting the area of the forest where they can hunt, thus slowly eliminating their way of life. You feel they should be left as is. Why is that?

Remember, for 95% of human history we were hunter-gatherers. If we lose that we lose our past. We're always so concerned where we come from, yet we do away with our links to the past and then we spend all this time and do research trying to reconstruct it. That, to me, is backwards. I don't see why on this big earth of ours there's not room to support hunter-gatherers.

Pygmy paradise: 'Song From the Forest'

Book Review

By Sue Gaisford, U.K. Independent, March 17, 1993

Louis Sarno was always going to be a pretty useless husband. He can't climb trees to fetch down honey or fruit; he can just about net a blue duiker, if it's a particularly dopey one, but he'd never spear one on the run if he tried for 50 years; and as for dancing, forget it. Yet half-way through his book the most beautiful girl in his world agrees to marry him. Her name is Ngbali and she dances in and out of his life in her blue knickers and pink plastic necklace, teasing and tantalising him right up to the very last page.

Ngbali is a Ba-Benjelle pygmy in the Central African Republic. Sarno is an American romantic from New Jersey. Idly listening to the radio one night in Amsterdam, he heard a recording of some pygmy singing and was transfixed. It was one of those rare moments that changes a life permanently.

Without any real idea of what he was doing, he bought a one-way ticket to Bangui, took a bus that was prophetically labelled 'Ainsi donc la vie' and found himself in the village of Bomandjombo. From there it was only a short distance to the pygmy settlement of Amopolo, which was to become his home.

It is an unexpectedly endearing story. Sarno's first reaction to the pygmies was shock and disappointment. For a start, some of them were quite tall; then they had a terrible craving for cigarettes, which they expected him to produce in vast numbers. They rather liked clothes and, worst of all, they seemed to do nothing at all. They fed him regularly on boiled tadpoles, which tasted like mud, and showed no signs of being the last and largest population of hunter-gatherers on Earth.

When he asked if he could record their music, they dutifully put on a show for him, having persuaded him that gallons of moonshine had to be provided first, but the music seemed not a patch on what he had heard on his radio in the Netherlands.

All this changed when his cash ran out and the forest spirits appeared. Little by little the people stopped treating him like Father Christmas and befriended him. At last they took him hunting and improved his diet with stewed antelope offal, roast porcupine and fat white grubs; they began to teach him their language and let him witness their real dancing and singing, which proved to be more wonderful than he had ever imagined. There is a problem with describing this ethereal music: he writes about its 'intricacy, subtlety and profound emotional content'; of the women's singing he says, 'gentle and warbly at first, their voices slowly blossomed into yodels of joy'; he describes the harp-zither, flute and earth-bow they use to create it, but to get any real idea of what it actually sounds like, you would probably have to send off for a cassette. There is a risk in that, of course. Look what happened to him.

He still lives there. Originally, he says, he thought the pygmies' concerns petty and trivial, but he has come to regard them as the most well-adjusted people in the world, whose undaunted preoccupation with enjoying each moment as it comes leaves them utterly free of neuroses. It is exhilarating to read about their forest life, essentially unchanged since it was described by the ancient Egyptians. They are forever setting up camp, hunting, fishing, conjuring up spirits, dancing, laughing, moving on, starting again. Their society is a loose, affectionate anarchy with just enough co-operation to ensure survival.

Louis Sarno's account of his strange journey away from modern civilisation is disarmingly frank and completely lacking in self-importance. Longing to be accepted by these people, but ashamed at his lack of basic skills, he appears to be the ultimate innocent in paradise.

When he attempts to persuade the reluctant Ngbali to move into his beehive hut, his arguments are immediately and sympathetically relayed to everyone else by his listening neighbours, with running commentary: 'Now she's sitting on the bed and he's sitting in the sand. Now he's moved in front of her but she's turned her head away.' It sounds comically comforting. Somehow, we know he will be all right.

Oka! Movie Review

By Peter Rainer, Film critic, The Christian Science Monitor, October 14, 2011

"Oka!" is loosely based on the unpublished memoir of ethnomusicologist Louis Sarno, who was born in 1954 in New Jersey and has lived with Bayaka pygmies in the southwestern part of the Central African Republic for more than 25 years as a welcome member of their community.

His 1995 CD-book "Bayaka: The Extraordinary Music of the Babenzélé Pygmies" inspired filmmaker Lavinia Currier, for whom he once acted as a translator for research about a documentary about pygmies.

"Oka!," which means "listen," is a fictionalized version of Sarno's experiences in Africa with his adopted family.

From a strictly narrative standpoint, "Oka!" is crudely fashioned. The story line has something to do with the exploitation of the pygmies' rain forest by an unscrupulous local Bantu mayor (Isaach De Bankolé). The acting by the professional actors, who also include Kris Marshall as Larry, the Sarno character, is overscaled compared with that of the actual Bayaka people who joined the cast as key performers.

Despite all this, "Oka!" is a fascinating movie with many free-form charms. (It's a bit reminiscent of the neglected 2000 film "Songcatcher," starring Janet McTeer as a turn-of-the-20th-century musicologist collecting folk songs in Appalachia.) At first I dreaded seeing another movie about a white Westerner uplifting the lives of black Africans, but this film presents the reverse scenario. Larry's life was transformed from the first moment he experienced Africa, and even though, at the beginning of the film, his doctor in New Jersey warns him that his failing liver cannot endure a return trip, he blithely reenters the fray, determined to record the native genius of the pygmies' sound.

The music has a complex 64-beat cycle. (Most Western pop music operates on a four- to eight-bar cycle.) Wielding his microphone on a long pole, Larry picks up the magic in the air. In one amazing sequence, he hides in the bush, with only the tip of his microphone protruding, as women in a nearby lake make music by pounding and splashing the water in percussive syncopation.

In addition to directing several other features and documentaries, Currier is also a board member of the World Wildlife Fund, and she has a receptive eye for the plangent beauties of the rain forests of the Congo River Basin. She also has an eye for the beauties of the African people, whom she films without condescension. The pygmies, averaging around 4-1/2 feet tall, are natural performers with an almost vaudevillian sense of play. Their teeth, sinister-looking at first, have been chipped into pointed, triangular shapes as marks of beauty. This takes some getting used to, but I found myself looking forward to the wide, happy grins of the tribal shaman Sataka (Mapumba), his wife, Ekadi (Essanje), and their flirty granddaughter, Makombe (Mbombi).

We don't need to have it demonstrated how difficult the lives of these people are, or how endangered is their way of life. The film itself subscribes to what Currier has described when she first contemplated her film: "In pygmy culture, they like to forget sad things and remember happy things, so I started to rethink that story from another perspective." Her film, mess though it is, captures an essential elation.

Find this movie Available on Amazon

Jim Jarmusch remembers Louis Sarno

By Carol Off, Journalist, CBC Radio, April 14, 2017

Writer Louis Sarno — who loved the music of Central African Republic's Bayaka Pygmies so much that he joined their tribe and lived with them for 30 years — died last week in New Jersey. He was 62.

Sarno first heard Bayaka music on the radio in Amsterdam in the early 1980s and was so captivated, he travelled to the rainforest village of Yandoumbe to learn more.

He spent the next 30 years of his life there, documenting and recording Bayaka music and culture, and writing about his experiences. He even became a member of the tribe, marrying two local women and adopting two sons, according to the New York Times.

Medical complications from hepatitis B, malaria, leprosy and cirrhosis brought Sarno back to his childhood home of New Jersey last fall, and he died of liver complication on April 1.

His lifelong friend, U.S. filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, spoke with As It Happens host Carol Off about how Sarno lived a full life, free of regrets. Here is part of their conversation.

Carol Off: Can you recall the last time that you spoke with Louis Sarno?

JJ: Yes, I saw him a few weeks ago. We sat and spoke for several hours together.

CO: And how did you find him?

JJ: It was quite shocking this time. Each year, he would return from Africa to the States for various reasons, the last years, often, some of them medical. And he was very, very fragile, and very kind of weakened.

CO: There's a quote from him that's so striking. He said: "I was drawn to the heart of Africa by a song. I boarded a plane that would take me into the equatorial heart of a continent where I did not know a soul on a quest for a music that might have been nothing more than a state of my imagination." What kind of a person does that?

JJ: Well, wow. He's very difficult to describe. He had a remarkable mind and imagination. He was really, really moved by music.

He was very, very interested in science and nature. He was one of the most gentle people that I've ever met.

We were in our late teens or early twenties when we first became friends, and he's one of the first people that I knew who was so careful of any living thing, for example, removing an insect to take it outside.

I remember I used to visit him when he was in graduate school at Rutgers for a while, and he lived in kind of a very bad building and his neighbours were some Appalachian people — some kids, I never saw the parents.

Every time I visited him, these little kinda hillbilly kids would always be in his apartment and he'd be telling them these incredible stories about seafaring pirates and sea creatures and things in the jungle. They were just riveted, and he had this way, really, with all people.

And he also had the most incredible sense of humour. I don't know if you have one person in your life who is like your laughing friend, a person you laughed the most with? For me, this was Louis. We used to laugh together so hard that we would get these incredible pains in the back of our heads.

CO: What's so fascinating about Louis Sarno is that when he went to find out about the Bayaka Pygmies ... he lived with them, he became part of their society. He had to penetrate and be on the other side of the glass. Did that come as a surprise to you, that he needed to do that?

JJ: No, it seemed keeping with his soul. He really liked the purity of their culture, even though he saw it becoming gradually devastated in many ways.

And the music is incredibly particular and exquisite.

I remember once, the amazing Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu, who I knew a little bit, he was visiting my loft in New York and I played him these recordings of the Bayaka that Louis had made, and he sat on the floor for about an hour with his eyes closed just absorbing this music. And afterward he said, 'This is the most elegant music I have ever heard.'

And now, thanks to Louis, the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford has all his archives of his recordings of this music.

CO: Can you tell us about his relationships?

JJ: He became very important to them, and so there were always a lot of children around him.

He never had anything, but they obviously really loved him, and I heard that this last time when he left the village, they all followed him for quite awhile. And that was the first time they ever did that. And I think that they were very concerned that they might not see him again.

CO: Did he ever regret the path that he chose?

JJ: No, never! [laughs]. And even when I last was with him and talking with him, you know, he said: 'I just want to get healthy enough to get back there.'

One thing I know about Louis is he definitely lived his life as he chose. And I have so much admiration for him, for how he lived his life, and I'm sure he regrets nothing.